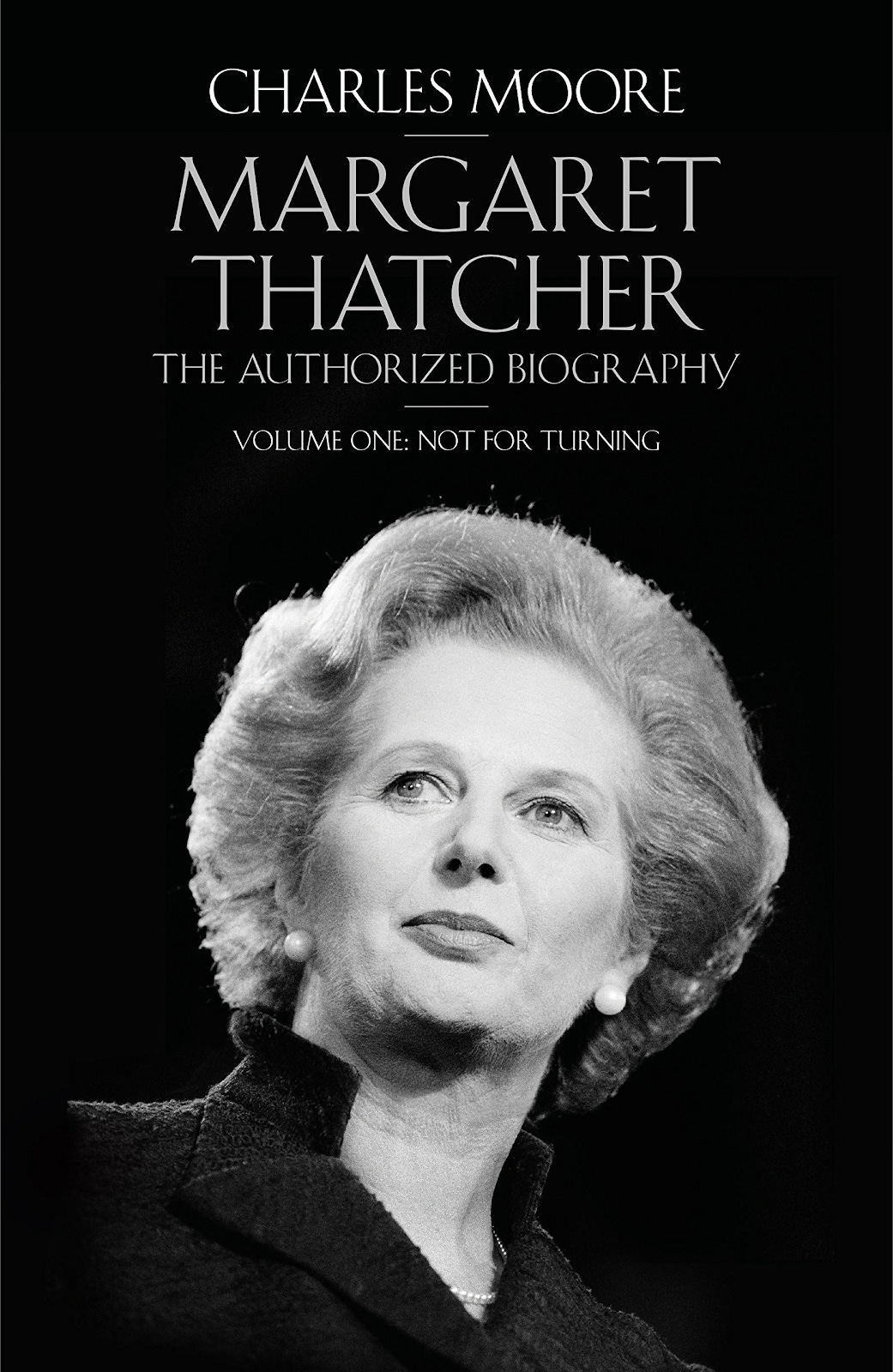

The first of a three-part review of Charles Moore’s three volume biography of Margaret Thatcher, beginning with Not for Turning.

Click here to read part two: Win Big or Go Home, and here to read part three: Two More Votes.

I want to tell you about a personal hero – or more precisely – personal heroine.

Figure 1. That final “e” is important

Margaret Thatcher may be the modern world’s greatest national leader, the closest in my lifetime, perhaps even my father’s lifetime, to the awesome standard of James K. Polk. Nicknamed “The Iron Lady” by the Soviets for her hardline stance in helping win the Cold War, what makes her truly remarkable is her transformation of British politics from a consensus of socialist sclerosis to a cross-partisan embrace of market economics.

Figure 2. The iron that won the Cold War, produced by free markets, could easily and appropriately have appeared on the set of Star Wars.

Charles Moore, a journalist during her heyday, tells her story over three volumes – and nearly three thousand pages – of an authorized biography that took over two decades and hundreds of interviews to complete. In our correspondence, we will discuss how she developed her views, how she dealt with her biggest challenges, and how she was finally betrayed.

Margaret adored her father, Alfred Roberts, a grocer active in the local politics of Grantham, an English town a hundred miles north of London then about 20,000 in population. Alfred had dropped out of school as a teenager to support his family but did not let a lack of formal education deter him from his interest in ideas: he was a voracious reader and active recruiter of interesting speakers for the local Rotary Club. Most significantly, Alfred was a lay Methodist preacher who inspired within his daughter a “puritanical desire for self-improvement” that celebrated the classic Protestant work ethic (“There is no promise of ease for the faithful servant of the Cross”) as well as a stridency of purpose (“God wants no faint hearts for His ambassadors.”)

The most telling anecdote of her childhood came when she petitioned her dad that she be allowed, like so many of her peers, to enjoy Sundays doing whatever she liked (or perhaps even wear a ribbon from time to time!). Alfred responded, “Margaret, never do things just because other people do them. Make up your own mind what you are going to do and persuade people to go your way.” Many would have bristled under this austere regime. Margaret thrived – and all the more so because Alfred gave her an opportunity rare among girls at the time: he encouraged her to regularly speak publicly, especially about their faith. His advice was simple and profound: “Have something to say. Say it as clearly as you can. That is the only secret of style.”

Figure 3. The best superheroes are advised by wise, older, British men named Alfred.

Extraordinary work ethic and clarity of communication would be defining features of her life – and they would lead to her first big opportunity. When her high school principal told her she didn’t have what it took to go to Oxford, Margaret replied “You’re thwarting my ambition” and convinced someone at the boys’ school to help her get what she needed. She was one of the few women to study chemistry – and she would later prefer to be known as the first Prime Minister with a science degree rather than the popular reference that she was the first female premier. But what would help her become PM was her active leadership of the Oxford University Conservative Association, where she made crucial early connections.

One of those connections recommended her, at age 24, to a local conservative party for nomination to Parliament. The British system and culture of politics is quite different from the United States, partially because Members of Parliament are actually expected to run the government departments whereas members of Congress only vote. As a result, candidates for Parliament are not necessarily from the places they stand to represent – nor even ever intend to live there. Indeed, at this time, Margaret was accepted by the local party because they were the hopeless minority and wanted an attractive, young, Conservative fighter to try to make a dent. If she performed well, she could expect to try to represent somewhere else where she might actually have a chance of winning. She ran well twice in Dartford, and cut Labour’s significant majority, but she did not come close to winning. The experience was good – she even was a youth speaker at a rally for Winston Churchill – but the most significant outcome was that she met her beloved husband Denis. Amusingly, Denis had been invited to a party meeting to meet “a very pretty girl” and was surprised to find “Good God, it’s the candidate!” Smitten, he volunteered to drive her around (she couldn’t afford a car) and soon gave her the surname she’s famous for: Thatcher.

What is striking in retrospect is that Thatcher was not yet the maverick she would become. Yes, the core was there – “a romantic belief in the greatness, and a sad lament at the decline, of her country” but she had not yet defined the path forward. Thatcher was for the sound running of government and began saying what she often would: “The Government should do what any good housewife would do if money was short – look at their accounts and see what was wrong.” But what conservative wouldn’t agree? More interesting is her early complaint that “There is a whispering – in fact, a shouting campaign in operation – that if the Tories get back they will take off all the [price and regulatory] controls, but this is untrue. It was the Tories who introduced the finest food rationing system during the war.” This was meant mostly as a criticism of the then-Labour government’s rationing – but it hardly sounds conservative to say “We actually do rationing much better!” And yet that was the position of the Conservative Party at the time.

The decades of “post-war consensus” had their origins in the coalition government of World War II – Churchill was satisfied to run the war and leave the details of domestic politics to his Labour partner Clement Atlee. After the war, both Labour and Conservatives accepted the welfare state and Keynesian economics as settled: the government should aspire to maintain full employment through high spending financed by high taxes, general regulation, and the occasional state seizure of entire sectors. The only difference may have been that Labour wanted to nationalize new industries while Conservatives were satisfied with the industries already nationalized.

Figure 4. Churchill once visited the men’s room at the House of Commons and, discovering Atlee at the urinal, proceeded to the opposite end. Atlee inquired, “Feeling standoffish today, Winston?” “That’s right,” Churchill replied, “Every time you see something big you want to nationalize it.”

Thatcher would soon be dissatisfied with such an arrangement. After over a decade of politicking, Thatcher had sufficiently shown her talents to be circulated on the Conservative Party’s official approved list of candidates they’d like to see in Parliament. A local party with a comfortable conservative majority gave her the nomination, though perhaps because the sympathetic chairman “lost” two of her opponent’s votes. In 1959, at age 34, she was finally a member of Parliament. Because the Conservatives were in power, she was soon given a job in government. Because she was so new, it was very junior. Because she was a woman, it was in the machinery of the welfare state, which the leadership thought relatively unimportant.

Thatcher initially wasn’t very happy with the assignment but the job “taught her how welfare worked, and did not work, and why government spent so much money.” And she started to make her mark. Moore observes that, “Combined with her lower-middle-class background, [being a woman] gave her a sense, which never left her, that she was living dangerously. To succeed, she knew she would have to do everything twice as well as the others, virtually all of whom were men. If she failed, no chums would save her.” When she objected to blindly signing off on paperwork, a civil servant objected “Bloody woman. Her job is to sign them, not read them.” Her boss would inquire, “She’s trouble. What can we do to keep her busy?” Eventually, as she rose to a point where she was considered for the Cabinet, the Conservative leader Ted Heath presciently lamented, “once she’s there we’ll never be able to get rid of her.”

The Conservatives would be thrown out in 1964 and then return in 1970, with Thatcher as Minister of Education. Her goal was to save meritocracy in schools. She failed. The problem was threefold. First, her own party was divided while Labour was united in opposition. She was a product of what were called “grammar schools,” an equivalent of America’s public magnet schools, where gifted children at the age of 11 were selected to pursue a separate, more academically-rigorous program. Moore notes their compelling features: “They represented excellence, they benefited from the exercise of parental choice, and they were the best ladder of advancement ever devised for bright children from poor backgrounds.” But less than 20% of children attended these selective schools – and those tied to the 80%, an overwhelming number for a democracy and necessarily including lots of frustrated Conservative Party members, did not like the diversion of scarce resources nor the feeling of being left behind. Her second problem was that control over schools was proudly decentralized and her role was essentially confined to sending a check. Moore relates that “In parliamentary answers to Education Questions throughout her time in office, Mrs Thatcher’s most common reply begins with the words: ‘I have no direct control…” But the third problem would become the most famous. The Conservatives were trying to cut spending across government and demanded that Thatcher produce cuts in her own department. Desiring to minimize any cuts to classroom education, she agreed to extend a previous Labour government decision to withdraw free milk from high schoolers to younger children. This caused an uproar that led to her first nickname: Margaret Thatcher, Milksnatcher. She retreated from the limelight, became abnormally accommodating to preserve her position, and quietly prepared to fight another day.

Figure 5. The opposition milked the controversy dry.

Over these years, in and out of government, Thatcher honed her views. Working on the nuts and bolts of the welfare state, she would conclude that “she wanted the state to mobilize to help the unfortunate, and always believed that there was no full private substitute for this, but she always feared two things – that the ‘shirkers’ would tend to benefit at the expense of the workers, and that the cost, if not carefully controlled, would produce national ruin.” She was sympathetic to one particular part of the post-war consensus articulated by Churchill’s adviser Lord Beveridge, who argued that “when someone did have to be given National Assistance, the ‘provision of an income should be associated with treatment designed to bring the interruption of earnings to an end as soon as possible’.” On the campaign trail, Thatcher would make one of her most famous observations, that socialism has “always succeeded in running out of other people’s money.”

And, really, public speeches were Thatcher’s tool to clarify her own thinking – at the end of her career, she would reflect “I have never knowingly made an uncontroversial speech in my life.” She would agree to speak on a topic of interest sometime in advance – and then she would “absorb almost any amount of detail” she could about the subject. And yet “Strong though she was on the detail, most of the time she articulated a purpose beyond it.” Building on her father’s lessons, Thatcher would learn “‘Every speech should tell a story or a fable’ and that ‘A speech is to be heard,’ a living performance which the speaker must enact with hands, eyes and voice as well as verbal content.” Thatcher was better at selecting and editing collaborators than writing speeches herself – but she was at heart the political equivalent of a method actor who obsessed about the meaning and presentation of her words.

In what may be described as her national party debut, Thatcher had been invited in 1968 to give a major speech outside the Conservative Party conference on the subject of women’s rights. She rejected that narrow subject – she was pleased by the opportunities offered a conservative woman but did not want to be confined. In another context, “in a sentence which summed up so much of her attitude to life, she declared, ‘Equity is a very much better principle than equality.’” She applied herself completely to the preparation of the speech, checking out over 30 books on conservative economics, philosophy, and history. She wound up presenting the moral case for markets: “The Good Samaritan had to have the money to help, otherwise he too would have had to pass by on the other side.” She would soon contrast this against the Labour position: “If you make it, I’ll take it”

Thatcher had come to the conclusion that “politics is a question of alternatives” but, remarkably, she was a subtle rebel. Throughout her entire legislative career, Thatcher only voted against her party leadership’s official preference once: to restore corporal punishment to criminals (a position, like her desire to restore the death penalty, supported by the grassroots but opposed by the elites). Thatcher signalled to the right-wing of the party that she was sympathetic through her speeches and private communications – but she was not one of its leaders, like Enoch Powell or Keith Joseph. Powell had dramatically gotten himself fired from Cabinet for giving a vivid speech about the need to rethink immigration and continued to throw verbal bombs from the back benches. Joseph remained in prominent party leadership but also had set up a think tank to critically reconsider Conservative Party modern orthodoxy.

In 1975, Ted Heath had been leader of the Conservatives for about a decade. He had lost an election in 1965, miraculously won another in 1970 in defiance of polls and expectations, then lost another in 1974 when he didn’t have a good answer to the heckler who cried “What can you do if you win that you can’t do now?” Heath was the epitome of the post-war consensus, even believing that the only way to deal with persistent industrial problems may be a grand coalition government with Labour. Moore observes that

“Government spending had risen from a 44 per cent share of Gross Domestic Product in 1964 to 50 per cent in 1969. That drift, the Tories had argued, had to stop and be replaced by a downward pressure and by a political direction which would be maintained. The Conservatives who won in 1970 were committed to a smaller state, and a freer economy, and to the urgency of these matters. They failed, and their failure created the conditions for Margaret Thatcher to become their leader.”

But that outcome was not at all obvious. Thatcher, a footsoldier, was going to be campaign manager for the real star: Keith Joseph. But Joseph hesitated, partly because challenging a sitting leader is risky and partly because of the reaction to his recent controversial speech about broken families in Britain’s lower classes. Thatcher then entered the race herself – but she was widely considered a stalking horse for Joseph. The tactic, well-recognized in British politics, was that her challenge would show the strength of Heath: if he won decisively, her career might be badly damaged but the real rightwing leadership could live to fight another day. If Heath won with only a small majority against such an insignificant candidate, then he could gracefully exit while the real leadership contest proceeded. Given Heath’s weakness, the joke was that the race was between a gelding and a filly. No one actually thought she could win.

Except, perhaps, her campaign manager, a brilliant Machiavellian named Airey Neave. Neave was a perfect example of the backbenches of the Conservative Party who had never gotten much love from Heath – and therefore knew exactly how to talk to many of his peers who shared the same disillusions. Neave kept Thatcher above the fray: he encouraged her to keep making smart speeches that demonstrated the courage of her convictions while arranging for her to spend time with key people. Meanwhile, Neave politicked: in a representative example, he flattered one disenchanted backbencher by saying “Margaret assumes you must have turned down a job offer from Ted.” “Why?” replied the backbencher. “Oh, because you so obviously should have one if you want it.” Even more effective than generating goodwill, however, Neave played on the hopes of all people skeptical of Heath for different reasons. Though he had a highly accurate list of where the votes were and he was aware that Thatcher was continuously gaining, Neave would tell people on the fence who really wanted someone else that she was short of what was needed to knock off Heath. When the vote happened, Thatcher beat Heath 130-119.

“The oldest, grandest, in many people’s eyes the stuffiest political party in the world had chosen a leader whose combination of class, inexperience and sex would previously have ruled her out. And it was not obvious that it had really meant to do so, or that it was confident of its choice.” But Thatcher knew what she was doing, insisting to the media on the very day of her election as leader: “You don’t exist as a party unless you have a clear philosophy and a clear message.” To the dismay of her competition, she quickly won over the party’s grassroots voters, declaring in a speech before their convention: “It is often said that politics is the art of the possible. The danger of such a phrase is that we may deem impossible things which would be possible, indeed desirable, if only we had more courage, more insight.” When Labour politicians were aghast at her expressing criticism of the UK while in the United States, she defiantly proclaimed: “It’s no part of my job to be a propagandist for a socialist society.” From then on, Moore notes “Mrs Thatcher could still be slowed down by appeals to the political danger of what she was trying to do, but nothing could stand in the way of the general direction of travel.”

British voters finally were offered a choice. Over three decades of the post-war consensus of socialist sclerosis culminated in the Winter of Discontent of 1978-1979. In just the last five years, the British pound had lost more than half of its value and inflation was still in the double digits. Labour was already embarrassed by having to apply for the largest loan in IMF history and now proposed to battle inflation by holding down public sector wages, including in many of the industries they had nationalized, hoping to inspire what remained of the private sector to do the same. But this angered the Labour Party’s extremely powerful union allies, who understood that if their wage increases did not match inflation, their purchasing power was being commensurately cut. Truckers, railroad workers, garbage men, manufacturers, and others went on strike, emboldened by the recent success of the almighty coal-miners, upon whom the nation depended, through a nationalized coal industry and amidst an international oil embargo, for heat. The post-war consensus had lost its shine. And the whole point of the Labour Party – created to give unions political power so as to achieve industrial harmony – seemed gone.

Thatcher supplied the alternative, best encapsulated in a political poster of the time said to depict some of the 1.5 million Britons out of work under the headline “Labour Isn’t Working.” In the 1979 election, the Conservative Party won a comfortable majority in Parliament, making Margaret Thatcher, as she preferred to be known, the very first Prime Minister with a science degree.

Figure 6. Click to buy Charles Moore’s three volume biography of Margaret Thatcher: Not for Turning (10/10); Everything She Wants (8/10); and Herself Alone (9/10). The first volume is the best, and from which much of this specific email is derived. Once Thatcher becomes Prime Minister, Moore chooses to address her life by topic rather than chronology, which is probably the right decision for understanding but is a little jumpy. Altogether, the biography can be forgivably over-comprehensive, is sympathetic but frank, and hopefully leaves you inspired by her example.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this review, please sign up for my email in the box below and forward it to a friend: Think – do you know any conservatives who might learn from one of the most successful conviction politicians of all time? How about any ambitious women? Or someone who appreciates modern history?

I read over 100 non-fiction books a year (history, business, self-management) and share a review (and terrible cartoons) every couple weeks with my friends. Really, it’s all about how to be a better American and how America can be better. Look forward to having you on board!