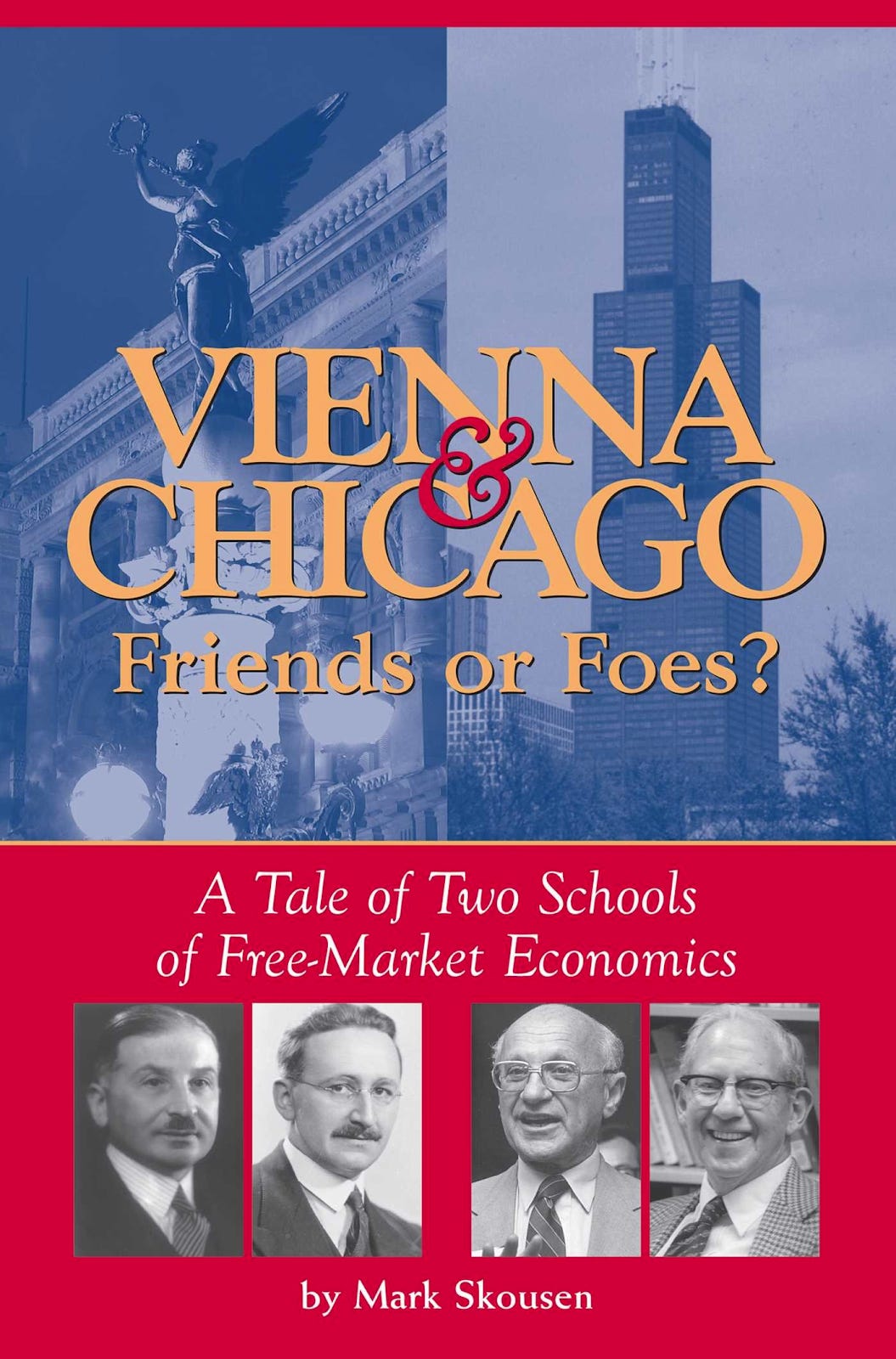

Part two of a three part review primarily of Vienna & Chicago by Mark Skousen. Click here for part one and here for part three.

Was self-identified libertarian Milton Friedman actually an outright “statist” or perhaps just “a technician advising the state on how to be more efficient in going about its evil work”? Both accusations were made by Austrian economist Murray Rothbard. The modern godfather of Austrian economics Ludwig von Mises once stormed out of a meeting of the ostensibly free-market-oriented Mont Pelerin Society, proclaiming “You’re all a bunch of socialists.” Meanwhile, Friedman himself once called Austrian (and fellow Nobel laureate) F.A. Hayek’s economics “very flawed” and “unreadable,” another time declaring before a surprised conservative forum that John Maynard Keynes was a better economist than Mises.

What accounts for the barbs exchanged between adherents of the two schools of economics associated with the right? Is this fight club merely a matter of personality clashes or petty differences over how many central bankers can dance on the head of a pin? Both schools are in favor of freer markets and have done much good to advance them - as Mark Skousen summarizes our last correspondence, “The Austrian and Chicago schools were born in the midst of crises in economic theory, at times when the classical laissez-faire model of Adam Smith faced unprecedented challenges from the critics of capitalism.” Each emerged as capitalism’s defender when it was needed: “The Austrians rescued classical economics from the socialist/Marxist threat in the late 19th century, while the Chicago school countered the Keynesian challenge of the 20th century.”

And yet Austria and Chicago have substantive and substantial disagreements in four areas: the appropriate methodology for resolving questions of economics, whether the government should ever intervene in a free market, how exactly business cycles work, and, most importantly of all, what is the appropriate way to manage our money.

Chicago and Austria’s first disagreement regards methodology, in particular, “should a theory be empirically tested?”

Austrians insist: No. This can be a shock when first encountered - but historical context can at least inform how they came to that position. In addition to meeting the challenge to capitalism set out by Marx, Austrians were also fighting the prevailing German-language scholarship that insisted that no general theory of economics applied across time and space. Unfamiliar to English audiences, the Historical School insisted that only a deep study of an individual period and place, its folkways and circumstances, could tell you about its particulars - and then only its particular particulars. Austrians wound up taking an extreme alternative view: the same principles of economics not only applied everywhere always but need not require any contemporary observation nor knowledge of history at all. Instead, good economic theory could be revealed through logical deduction, “built upon self-evident axioms, and history (empirical data) cannot prove or disprove any theory, only illustrate it, and even then with some suspicion.”

Figure 1. While it’s amusing to think about a universe in which the laws of economics do not apply across time and place (where, for example, opportunity cost no longer exists, you can always simultaneously do everything you want with your infinite time and resources!), you’ve got to hand it to the German Historical School - if every single particular time and place needs its own expert, it’s much easier to get tenure.

And yet that is not the only aspect of the Austrian position that is likely to sound strange to new ears. You may recall the Austrians pioneering the subjective theory of value which has now become part of mainstream economics - the idea that goods and services will be valued differently by different people at different times. Well, the modern Austrians can take that theory much further: Israel “Kirzner once insisted that it is impossible to determine whether a wealthy American making a million dollars a year is ‘better off’ than a French peasant making $200 a year” - because who is to say that the French peasant isn’t delighted with his condition and and the American millionaire miserable?

In contrast, “in his Nobel Memorial Lecture in 1976, Friedman claims that ‘there is no ‘certain’ substantive knowledge,’ only testable hypotheses.” Skousen notes that appropriately inscribed in front of the Chicago Social Science Building is a quote from Lord Kelvin, “When you cannot express it in numbers, your knowledge is of a meager and unsatisfactory kind.” One of the founders of the Chicago School, Frank Knight, “inspired the next generation to ‘challenge everything’ and to reject any idea that lacked logic or empirical support.” Chicago subsequently earned its reputation (and its cornucopia of Nobels) by running the numbers on things - and was able to be a force for free markets against Keynes because its numerical case was so overwhelming. Nobel laureate George “Stigler even suggests that professional empirical work (“scientific training”) is precisely what has led economists to become more ‘conservative’” - indeed, that was the experience of many of the Chicagoans themselves, starting from Keynesian premises, discovering they didn’t work, and altering their hypotheses. Chicago suspects that this methodological dispute is the core of all the others:

Friedman blames Mises’s methodology for the in-fighting between the Austrian and Chicago schools. “Suppose two people who share von Mises’ praxeological view come to contradictory conclusions about anything. How can they reconcile their difference? The only way they can do so is by a purely logical argument. One has to say to the other, ‘No, you made a mistake in reasoning.’ And the other has to say, ‘No, you made a mistake in reasoning.’ Suppose neither believes he has made a mistake in reasoning. There’s only one thing left to do: fight.”

Skousen gives his own verdict: “To be quite frank, Misesian epistemology set back the advancement of Austrian economics and delayed the opportunity to make serious contributions to the discipline.” As economic academia became more and more numerical (and more and more Keynesian), the Austrians were left behind and declined to adjust their ways. Whereas Columbia PhD Murray Rothbard refused to join professional economic associations, contribute to academic journals, or climb the ranks of traditional tenure, Columbia PhD Milton Friedman did all that and more. Skousen cites one estimate that less than 2% of academic economists are Austrian.

Figure 2. Chicago Phone cheaply and proudly offers you unlimited data. Austrian Telecoms freely hectors you for why the heck you’re on your phone when a perfectly good tin can and wire will resolve your problems.

But since when did conservatives blindly accept the consensus of academics? Let’s take a closer, nuanced look at the Austrian defense and counterattack. Running the numbers on things sounds very scientific - but is social science really science? Von Mises student and Princeton professor Oskar Morgenstern, the co-founder of game theory, “wrote an entire book questioning the accuracy of economic data” and warned “that most economic data is highly unreliable and subject to manipulation and error.” Liberal Robert Kuttner insists “Departments of economics are graduating a generation of idiots savants, brilliant at esoteric mathematics but innocent of actual economic life.”

What if something is not easily captured by data or not easily modeled from it? Austrians advise humility in dealing with the vast complexity of the human condition - “An astronomer can know the exact time the sun will come up in the morning, but can anyone predict precisely when a student will get out of bed in the morning?” Can anyone consistently predict the movements of the infinitely more complex economy? (The evidence strongly suggests no. Not even the Fed, with vast data and substantial power, makes especially accurate predictions). How should we track inflation across the economy? (Our government’s favored index does not include three notable categories: housing, healthcare, and education. What do you spend the most money on?) What if the data is just plain wrong, due to innocent error or self-interested parties altering numbers for their own benefit? How much do you trust polling to project election outcomes? The Soviet Union infamously published rosy economics statistics that caused even skeptical conservatives to fear that we’d be buried. Ratings agencies infamously over-graded subprime mortgages to sustain business.

Figure 3. Imagine if you were a clothing company that calculated the average height of men based on their self-reporting on dating apps.

What if data is easily misinterpreted? As the old saying goes, figures lie and liars figure. What if a statistical snapshot is not representative of dynamic changes? Do better grade averages versus decades ago reflect smarter students or easier grading? Do generally lower prices in an economy represent the benefits of increased productivity, the mismanagement of the money supply, or what?

What if the data gives decision-makers or grand-theorists a false sense of confidence that they know what is going on? Mathematicians can become intoxicated by their arcane powers of unique understanding, applying their bespoke optimal solutions without realizing unintended consequences. Does anyone beyond an over-educated progressive have any hope that government bureaucrats can adeptly employ econometric forecasting models to figure out how much profit is necessary to sustain innovation and then skillfully adjust taxation on the remainder for optimal outcomes? F.A. Hayek advised, “The curious task of economics is to demonstrate to men how little they really know about what they imagine they can design.”

Figure 4. Hong Kong, ironically a favorite polity of Milton Friedman’s, intentionally kept as little data as possible on its economy - its British administrator feared that what gets measured gets managed, and he wanted to ensure maximum economic freedom (his success dramatically enriched an island without natural resources)

Austrians are skeptical that truth is a bigger driver than fashion in the popularity of ideas among academics - after all, the Austrians were in the wilderness for decades as the world embraced Keynes. For the Austrians, no amount of numerical gobbledygook could divert their critique that Keynes was reasoning from false premises. Get the premises right, Austrians insist, and the correct economic policy will flow from there. Mises insisted, “History speaks only to those people who know how to interpret it on the grounds of correct theories.”

Figure 5. Speaking of false premises, I was once on an American subway near a foreign couple trying to make sense of the metro map. A friendly young woman, sensing their confusion, intervened to help them get confident in when to get on and off the trains. She then asked where they were visiting from. The gentleman replied in a thick accent, “Ve are from Austria!” The woman lit up with excitement: “That’s amazing! I love kangaroos!”

Some Austrians suggest there is a hidden debate going on amidst this discussion of methodology where the Austrians are most interested in morality and the Chicagoans are most interested in efficiency, where the Austrians advocate for what’s right and the Chicagoans advocate for what will make us all rich. Unfortunately, by only occasionally deigning to engage in numerical and historical defenses of their ideas, the Austrians often argue with one arm tied behind their back. To quote Churchill, “However beautiful the strategy, you should occasionally look at the results.” But the remarkable aspect of the Chicago-Austria dispute is that Chicago’s relentless drive for data has moved it closer to what the Austrians were arguing all along.

At one point in his book, Skousen makes an analogy that the various prominent schools of economic thought reflect different levels of faith in the invisible hand of the free market, “a certain degree of confidence that, left to their own devices, individuals acting in their own self-interest will generate a positive outcome for society”: Marxists (appropriately) have zero faith, Keynesians a little, Chicago a lot, Austrians complete. The difference between a lot and complete is probably easiest to see in disagreements about how often (if ever) the government should intervene in the free market and, in particular, antitrust: what should the government do about a private monopoly? As Skousen puts it, “Is Adam Smith’s system of natural liberty sufficiently strong to break up monopolies through powerful competitors, or is government necessary to impose antitrust policies when appropriate?”

Austrians, predictably, recommend the government do nothing. To them, “market failure” is practically an oxymoron - and actually more often revealing of some antecedent government intervention. As Murray Rothbard thundered, “The only viable definition of a monopoly is a grant of privilege from the government… What [antitrust laws] accomplish is to impose a continual, capricious harassment of efficient business enterprise.” Skousen reports, “According to the Austrians, it is impossible to determine the optimal number of firms in an industry... The best model is the ‘market test,’ a discovery process of trial and error, where each industry determines its own optimal size and pricing structure through competitive profit seeking.” Rather than antitrust, Austrians say the government needs to go in the opposite direction - maximum deregulation - because “an open market allows any firm with sufficient capital and ability to enter an industry and create whatever products and services consumers desire. While the market test allows market barriers, such as minimum capital requirements, to restrict entry, governments should impose no artificial barriers, such as special licenses and import quotas.”

Figure 6. One British libertarian, Antony Fisher, believed that markets could even do a better job than government protecting endangered species. He attempted to farm green sea turtles, selling their meat so that the profits would motivate him and others to breed more. Angry environmentalists shut him down, ensuring the future of turtles was left with bureaucrats, not entrepreneurs.

Initially, Chicago was rather enthusiastic about conventional “big is bad” antitrust in order to preserve and enhance business competition. But Chicago eventually concluded that antitrust was usually more trouble than it was worth and that the goal really ought not to be pure competition but maximum consumer welfare, most easily analyzed in the prices consumers pay. Chicago school scholars predictably “amassed considerable data to demonstrate surprising price flexibility and competition among large companies, concluding that industry concentration did not necessarily lead to monopolistic pricing. Stigler concludes, ‘Competition is a tough weed, not a delicate flower.’” Heretically, even an Austrian, Dominick Armentano, did quite a bit of historical research to turn the tide, finding that the supposed robber barons of the 19th century “drastically cut prices as they expanded output rapidly,” that “most antitrust cases are brought by private firms against their rivals” (not by consumers), and that “business collusion turns out to be a myth since high fixed costs and legally open markets encourage price cheating and secret discounts to customers.” Ultimately, Chicago is cautiously antiantitrust. Yet another Nobel laureate “Gary Becker sees it as a tradeoff. In his view, ‘it may be preferable not to regulate economic monopolies and to suffer their bad effects, rather than to regulate them and suffer the effects of political imperfections.’” Indeed, “the Chicago school has not abandoned all forms of antitrust policy… most Chicago economists support policies prohibiting price fixing and horizontal mergers.” That a monopoly might hurt consumer welfare worse than government intervention is still plausible to Chicago, especially in the not quite free markets we enjoy. To Austrians, the monopoly can sustain itself only if the government restrains competition on its behalf - and that typical trustbusters miss the first principles of what makes the free market work.

Figure 7. Monopoly’s rules are different from monopoly rules. You and your thumbtack don’t just randomly traverse the world, rolling a die to see which property you might buy or what company you might have to pay (for nothing in return). Indeed, your world is not nearly so limited as a board and you might find yourself shopping for better options just beyond its edges or perhaps traveling to another board altogether. There is one notable thing about Monopoly, though: its funny money has held its value better than the American dollar.

Of course, one of the biggest invitations for government intervention in modern economics is a recession. By merely working and living, everyone has a sense that there are good times and bad in the economy. Most economists think that there’s no discernible pattern to them (or perhaps they’re unknowingly with the German Historical school about particular particulars). Keynes hypothesized that inscrutable and mysterious animal spirits drove investors and consumers to do what they do unless a benevolent government prods them in the right direction. Marx thought recessions and depressions were all part of the ravaging disease of capitalism and that they were only going to get worse and worse until the workers’ revolution. The Austrians have a specific theory that is not accepted across the economic profession, wherein the drunken hazes of booms are followed by the correctional hangovers of busts. In the Austrian business cycle theory, the booms are fueled by over-aggressive bankers (often of the central variety) who lend out too much money at rates that fool consumers into overspending and capitalists into malinvestments. When money is cheap to acquire, everyone is tempted by (marginal!) buys that wouldn’t normally make sense. Busts are the inevitable outcome where people realized their mistakes.

Chicago, as ever, is concerned with the money supply (though there’s some newer Chicago commentary about how the business cycle is mostly a distraction from long-term growth and governments get too myopically focused on what’s happening now v. over decades). Friedman did try to run the numbers on Austrian business cycle theory and did not find a correlation between the depth of recessions and the height of the preceding expansion (though Skousen questions this study). In an unrelated paper, “Friedman argues that an economic model should be judged solely on its predictive power, “the only relevant test,” not the realism of its assumptions.” And he didn’t think Austrians met the test. Generally, Friedman thought that the market was efficient, money traveled fairly easily, and that a free economy will quickly self-erase distortions and malinvestments. In perhaps Friedman’s most famous analogy, he suggested that if a helicopter were to throw cash out its windows, doubling every person’s cash in a small town, it would raise prices but not productivity. “The additional pieces of paper do not alter the basic conditions of the community.” Friedman said. What Friedman instead worried about was inflation accelerating or behaving unpredictably.

The Austrians reject the helicopter analogy as terribly inapt: even if money in a community is doubled, who is to say that distributing it from a helicopter would double each community member’s money? “‘Who gets the money first?’ is the overwhelming question the Austrians want answered.” If every citizen was sent a check, Friedman’s analogy might be closer to the point. But if the money is dispersed through the banking system (as it most often is in a monetary expansion), then people might be inclined to take on more debt than they really should, triggering the boom of overspending and malinvestments. Austrians charge that money does not travel as easily as Friedman thinks - it’s not easy getting your cash out of a multi-year building project all planned with particular economic conditions in mind. “Austrian capital theory predicts that the further removed the production process is from final consumption, the more volatile are prices, employment, inventories, and output, due to the time value of money (interest rates).”

To better understand the two sides, consider the Great Depression. Whereas the Austrians think that the roaring 1920s obviously constituted an irresponsible boom, Friedman wasn’t so sure: “monetary inflation was modest, prices were relatively stable, and economic growth was reasonably high.” When Austrian Rothbard wrote a book about the Depression, he used “eccentric” and novel definitions of the money supply to try to sustain the Austrian theory without convincing many. But take a look at the stock market: the 15.6x price per earnings of stocks was actually below what the long run average would become and not far above what the previous average had been. Yet Skousen notes that national output averaged 5.2% a year but that an index of the S&P grew 18.6% during the 1920s - and, indeed, while GDP grew “only 6.3% from 1927-1929” stocks gained 82.2% as investors borrowed more and more money to buy in. Contemporaneously, the Fed, for better or worse, raised interest rates to curb investor borrowing and speculation.

Everyone agrees that the beginning of the Great Depression was accompanied by significant deflation. The Austrians think that this was a vital cleansing of the system and that the government’s attempts to meddle, from Hoover’s tariffs to FDR’s New Deal, sustained the downturn. Chicagoans believe that the deflation turned a recession into a depression and that the Fed needed to expand the money supply rather than tightening credit (and, more controversially, that the federal government probably should have run deficits and even bailed out commercial banks to try to save the system). While Chicago’s narrative has become the accepted conventional one, Austrians are aghast at the prospect that pumping money into the economy would have done anything other than send wrong signals to consumers and capitalists.

That being said, there are some interesting and perhaps unexpected areas of agreement. If banks had been required to either hold all of their customers’ money to be available at any time or else sell their customers bonds through which they could collect interest, then there’d be no bank runs nor much of a crisis (This is called a 100% reserves requirement, or single-purpose banking). While liberals have often blamed the inflexibility of the gold standard, Milton Friedman instead defends it, arguing that if the government had allowed it to function as it intended, we would have allowed the inflow of gold into government vaults to grow the money supply - thus averting the deflationary crisis. Austrian “Richard Timberlake agrees that the Great Depression could have been avoided entirely if the U. S. had been on the classical gold standard, noting that gold reserves increased to 4,900 tons in 1933 and 18,000 tons in 1940.” But while Friedman preferred a 100% reserve requirement, he could also, to the consternation of the Austrians, “predict that with government deposit insurance and a seasoned central bank, the economy is largely ‘depression proof.’”

Where we go from here will be explored in another email but this final point gets to the heart of the differences between Austria and Chicago. While Austrians have criticized Chicago for its impurities, “Friedman and his followers have been equally critical of the Austrian school for… lack of practical advice to solve problems in government and society—in short, for its unwillingness to get their hands dirty in the practical world of politics.” Ultimately, “Chicagoans often call for second-best solutions” - the difference between a reluctant acceptance of deposit insurance and 100% reserves, between a low flat income tax and the abolition of the income tax, between a negative income tax that incents welfare-recipients to get back to work and the abolition of welfare. Wherever you fall, you can learn from both.

Figure 8. Click here to acquire Mark Skousen’s Vienna & Chicago, a good overview and introduction to its subject matter. If you have not already, check out the entertaining and insightful rap battles between Marx and Mises, Keynes and Hayek.

Figure 9. Click here to acquire Milton Friedman’s Free To Choose (also a miniseries well-worth watching), a powerful introduction to Chicago by its most famous member. Click here to acquire Howard Baetjer’s Free Our Markets, a modern introduction to the Austrian way of thinking.

PS. One word on supply side economics. Not strictly an entire school, it’s most famous for the Laffer Curve scribbled on a DC hotel napkin that suggested that lowering taxes could actually increase revenue. Expanding on that principle, supply siders have advocated for deregulation and lesser taxation to spur productivity. Because supply siders are always in favor of tax cuts as a solution to practically any problem, they are quite popular among Republicans. In principle, Austrians and Chicagoans are also in favor of lower taxes and deregulation. But Austrians are skeptical of the supply-sider claim to find some sort of tax equilibrium and fear that supply-siders really don’t care about deficits. Though supply-siders have occasionally voiced enthusiasm for somehow connecting the dollar to gold, Murray Rothbard thought they were “‘old-fashioned populists’ who favor promoting inflation and cheap money.” (Rothbard, though, has his own quirks, such as opposing a simple tax code because it would make the government's job too easy.) Friedman proclaimed he was “in favor of tax reductions under any circumstances, for any excuse, for any reason, at any time” - partially with the hope that less money would spur the government to shrink, but his research indicated that short-term tax decreases wouldn’t spur the economy. Naturally, he was also concerned that supply-siders were not concerned enough with the money supply.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this, forward it to a friend: know anyone interested in economics or history? How about someone who wants limited government? Or do you know anyone who ever uses money to pay for things?

If you’ve received this email from a friend and would like more, sign up at www.grantstarrett.com or shoot me an email at grant@grantstarrett.com with the subject “Subscribe.” I read over 100 non-fiction books a year (history, business, self-management) and share a review (and terrible cartoons) every couple weeks with my friends. Really, it’s all about how to be a better American and how America can be better. Look forward to having you on board!